BRAND NEW: Rob49 - WTHELLY #hot21radio

BRAND NEW: Rob49 - WTHELLY #hot21radio BRAND NEW: Sleepy Hallow - Girls like girls #hot21radio

BRAND NEW: Sleepy Hallow - Girls like girls #hot21radio BRAND NEW: Ari Lennox - Soft girl era #hot21radio

BRAND NEW: Ari Lennox - Soft girl era #hot21radio BRAND NEW: Pluto & YK Niece - Whim whamiee #hot21radio

BRAND NEW: Pluto & YK Niece - Whim whamiee #hot21radioWhy Hip Hop is a Great Hobby for College Learners #hiphop

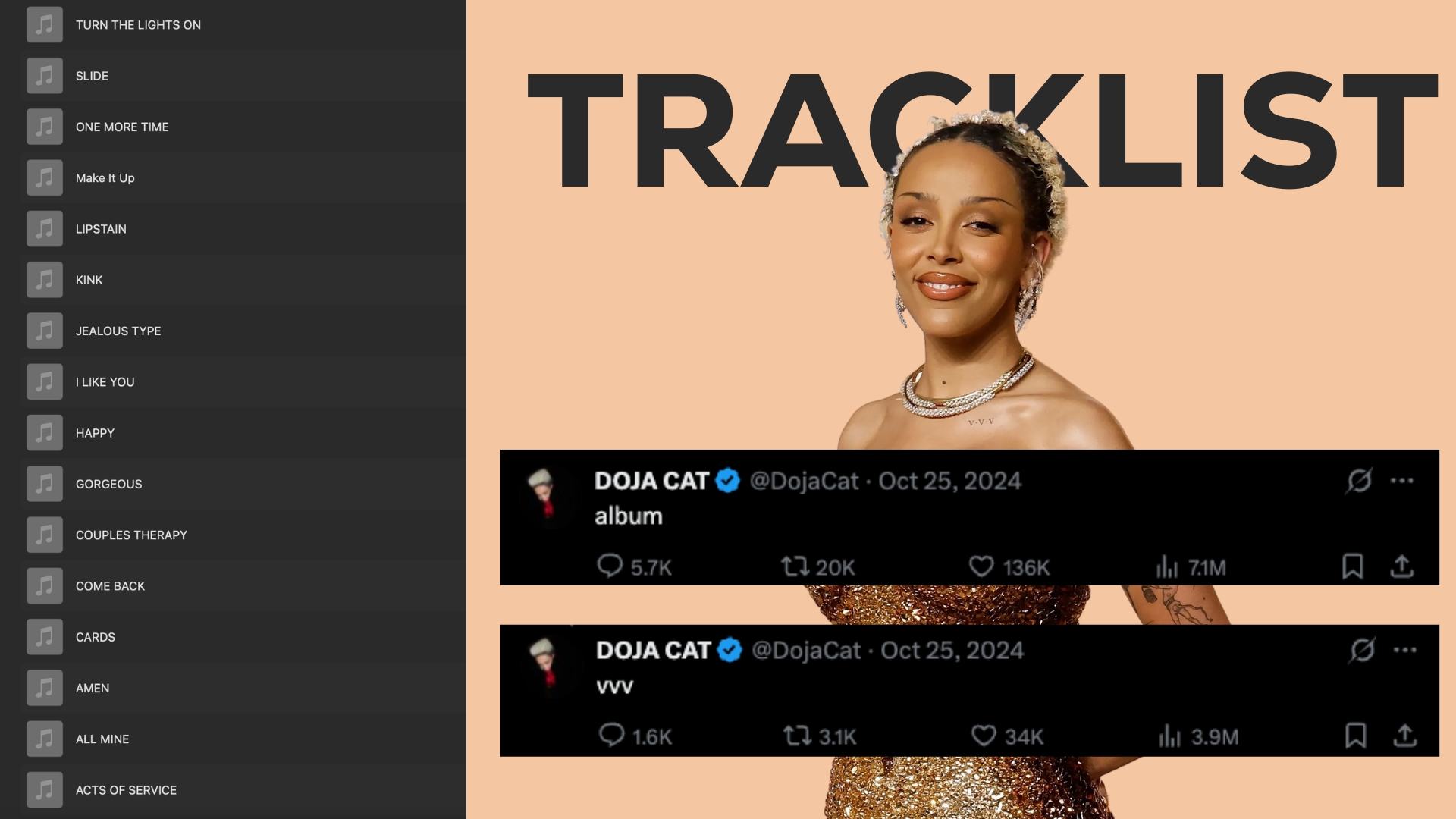

Doja Cat Teases Tracklist For Upcoming Album #DojaCat

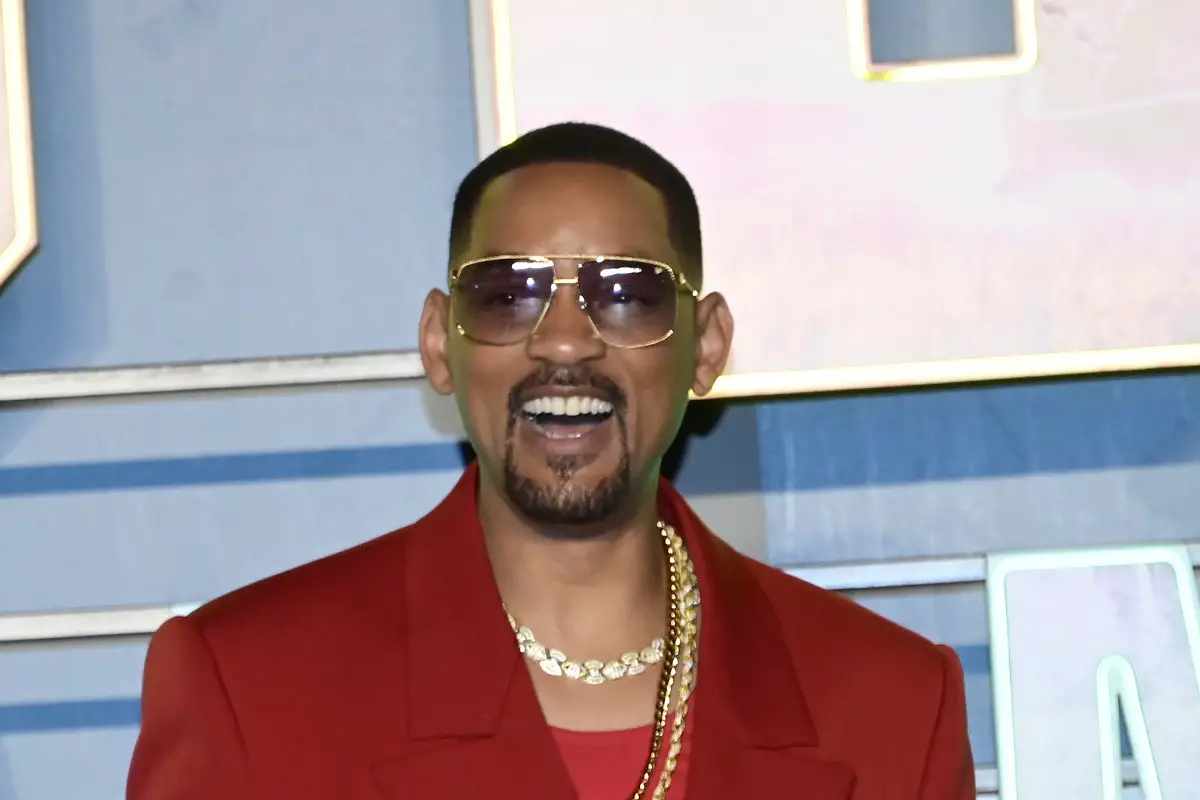

Doja Cat Teases Tracklist For Upcoming Album #DojaCat Rap’s New Renaissance: Why Older Hip-Hop Artists Are Thriving #hiphop

Rap’s New Renaissance: Why Older Hip-Hop Artists Are Thriving #hiphop Post Malone Closes Coachella With Headlining Set Blending Hip-Hop and Country #hiphop

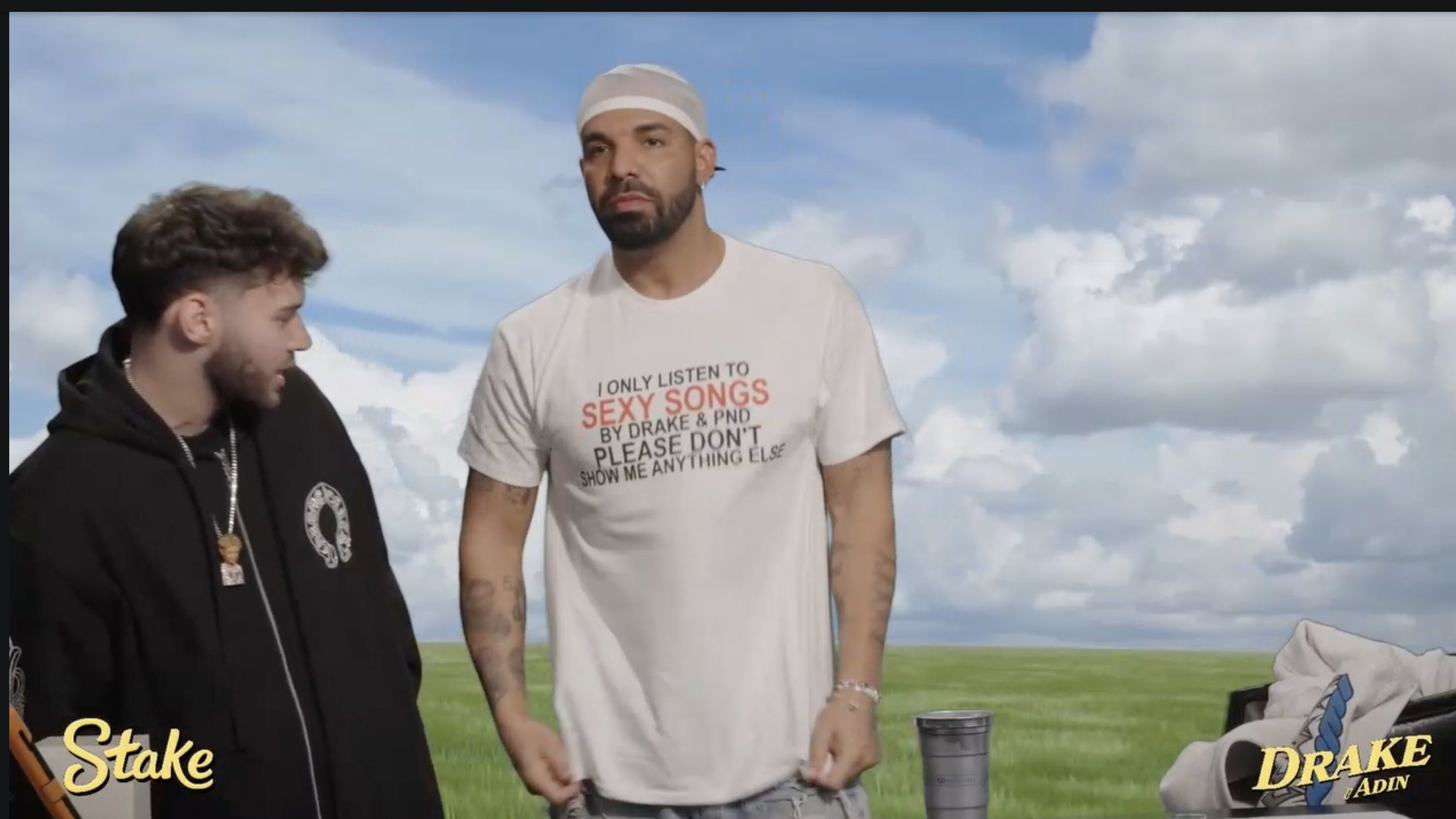

Post Malone Closes Coachella With Headlining Set Blending Hip-Hop and Country #hiphop Drake Confirms During Adin Ross Stream He’s Working On A New Solo Album #Drake

Drake Confirms During Adin Ross Stream He’s Working On A New Solo Album #DrakeHow to Watch Drake and Adin Ross' 'Stake vs. Drake and Ad... #Drake

Hell’s Kitchen review – Alicia Keys jukebox musical is a marvel #AliciaKeys

The Public Theater, New YorkThe star helps craft a show-stopping semi-autobiographical off-Broadway musical that brings the house downAh yes, the jukebox musical. That darling of fat-cat Broadway producers looking to make a quick buck by bringing a beloved songbook to life and packing the house night after night. Leaning on chart-topping numbers strung together via minimal dialogue, these mix-tape shows can also feel slapdash and witless, so much that the New York Times critic Jesse Green called jukebox musicals “the cockroach of musicals”.Hell’s Kitchen, Alicia Keys’s live-wire theatrical adaptation of her own hit list, puts the rest of the genre to shame. Over a dozen years in the making, the show, which makes its off-Broadway debut at the Public Theater (where Hamilton had its original run), is no rewarmed songbook. It’s a surprisingly loose-limbed and rousing celebration of love, music and a pre-TikTokified New York City, directed by Michael Greif (Rent, Dear Evan Hansen) and overseen by Keys, who had a hand in everything from the fly-girl dance routines to the casting of understudies. A recent preview performance had members of the audience losing their minds, raising their arms in the air mid-song and wiping tears from their eyes between numbers. Continue reading...

A h yes, the jukebox musical. That darling of fat-cat Broadway producers looking to make a quick buck by bringing a beloved songbook to life and packing the house night after night. Leaning on chart-topping numbers strung together via minimal dialogue, these mix-tape shows can also feel slapdash and witless, so much that the New York Times critic Jesse Green called jukebox musicals “the cockroach of musicals”. Harmony review – Barry Manilow’s Broadway musical lacks magic Read more Hell’s Kitchen, Alicia Keys’s live-wire theatrical adaptation of her own hit list, puts the rest of the genre to shame. Over a dozen years in the making, the show, which makes its off-Broadway debut at the Public Theater (where Hamilton had its original run), is no rewarmed songbook. It’s a surprisingly loose-limbed and rousing celebration of love, music and a pre-TikTokified New York City, directed by Michael Greif (Rent, Dear Evan Hansen) and overseen by Keys, who had a hand in everything from the fly-girl dance routines to the casting of understudies. A recent preview performance had members of the audience losing their minds, raising their arms in the air mid-song and wiping tears from their eyes between numbers. Keys, the Grammy-winning and classically trained R&B star, loosely based the story on her Manhattan childhood. The erratically present father, powerful and possessive mother, and life-changing piano teacher are all there (played, respectively, by Brandon Victor Dixon, Shoshana Bean and Kecia Lewis, who together have enough star power to light up a constellation). At the production’s center is Maleah Joi Moon, the radiant and angel-voiced 21-year-old newcomer who fell from the heavens (New Jersey, actually) and plays 17-year-old Ali. She lives with her mother in Manhattan Plaza, a subsidized apartment complex in the grimy midtown neighborhood from which the show takes its name. Donning the baggy pants and boxer shorts combo and Timberland boots that were standard city-girl attire in the 90s, and alternately channeling childlike giddiness and hormone-fueled rage, Moon is an unparalleled avatar of the torment of being 17. Like Persephone, our heroine is unable to separate from her mother but simultaneously unable to resist the urge to stray from her. She’s on the verge, and the production gives voice to the seemingly fresh hell of late adolescence. A fast talker who gave up her artistic dreams long ago, around the time Ali was born, Jersey still puts dinner on the table every night at 6pm before heading out to work. On her own, Ali finds much to explore at close range, including a new love for playing the piano, and a fixation on a slightly older boy called Knuck (Chris Lee), a self-identified “thug” whose singing voice could lure an entire flock of Disney birds to come circling overhead. One of the most striking components of this show is its embrace of contradictions. There are no villains, no princesses. Ali’s struggle is two-sided: she longs to cling to her mother, and to set herself free. Said to be the most expensive production ever staged at the Public, Hell’s Kitchen employs a jubilant cast of dancers (with choreography by superstar Camille A Brown) and set design that brings pre-millennial Manhattan bohemianism to boisterous life. Wall projections (designed by Peter Nigrini) manage not to call attention to themselves but establish a sense of a world, from the street exteriors to the elevator rides that whoosh up and down Ali’s 40-odd-story playground. Ali is a 90s-era Eloise at the Plaza, keen eyed and tuned into the stories unfolding around her. And, of course, the Alicia Keys hits keep coming (as do a handful of new compositions). Lyrics and rhythms have been refreshed for the purposes of the story, and not a single tune feels obligatorily wedged in. Each number is a new invitation to lose yourself in emotional overwhelm. This is a work suffused with angst and pain, and the performances give new meaning to hits like Fallin’, Empire State of Mind and Girl on Fire. The run is sold out, but it’s hard to imagine there won’t be an opportunity to see it. If this show doesn’t bullet to Broadway, we should all give up. Read more