Latest News

BRAND NEW: Rob49 - WTHELLY #hot21radio

BRAND NEW: Rob49 - WTHELLY #hot21radio BRAND NEW: Sleepy Hallow - Girls like girls #hot21radio

BRAND NEW: Sleepy Hallow - Girls like girls #hot21radio BRAND NEW: Ari Lennox - Soft girl era #hot21radio

BRAND NEW: Ari Lennox - Soft girl era #hot21radio BRAND NEW: Pluto & YK Niece - Whim whamiee #hot21radio

BRAND NEW: Pluto & YK Niece - Whim whamiee #hot21radioWhy Hip Hop is a Great Hobby for College Learners #hiphop

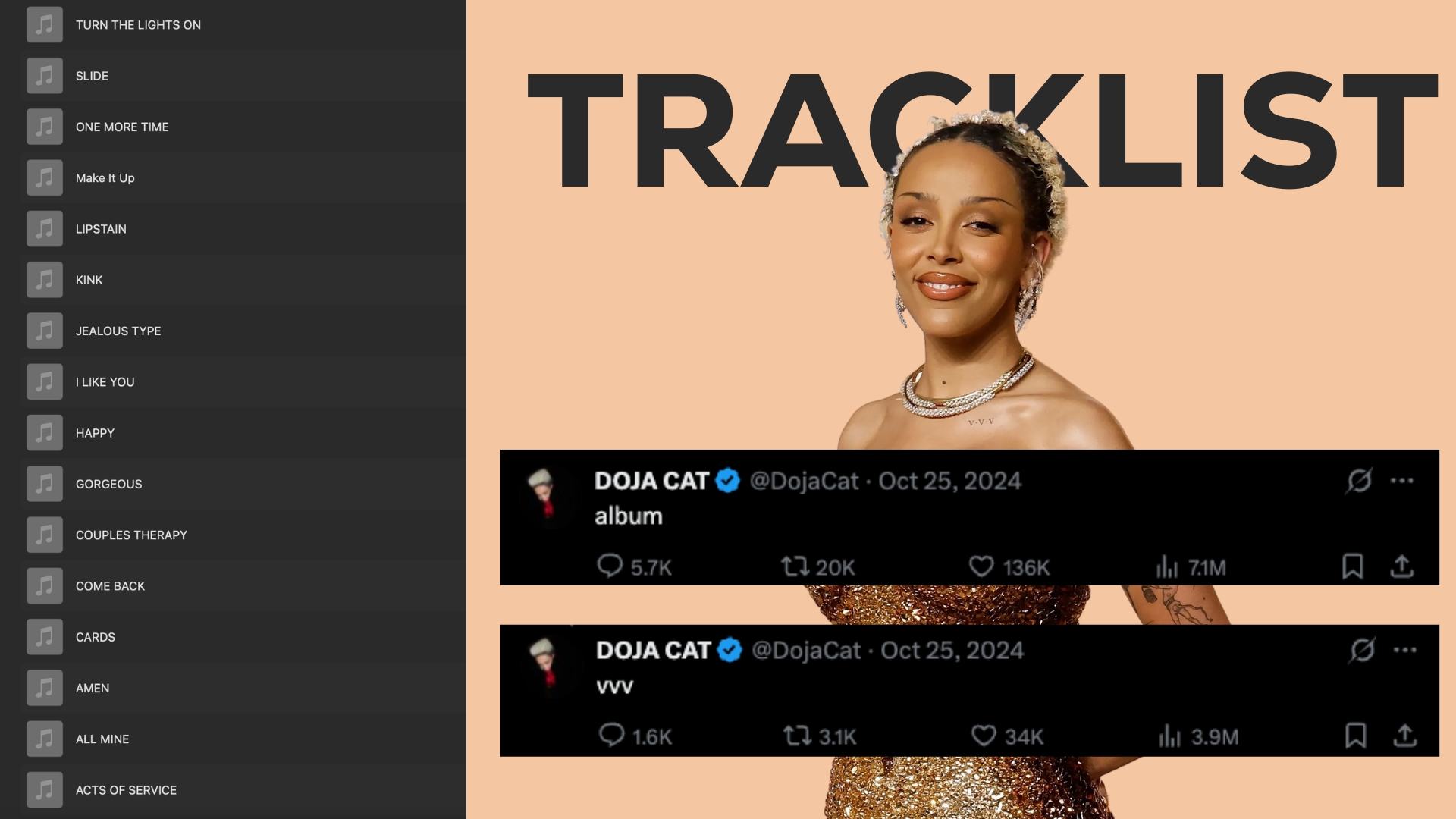

Doja Cat Teases Tracklist For Upcoming Album #DojaCat

Doja Cat Teases Tracklist For Upcoming Album #DojaCat Rap’s New Renaissance: Why Older Hip-Hop Artists Are Thriving #hiphop

Rap’s New Renaissance: Why Older Hip-Hop Artists Are Thriving #hiphop Post Malone Closes Coachella With Headlining Set Blending Hip-Hop and Country #hiphop

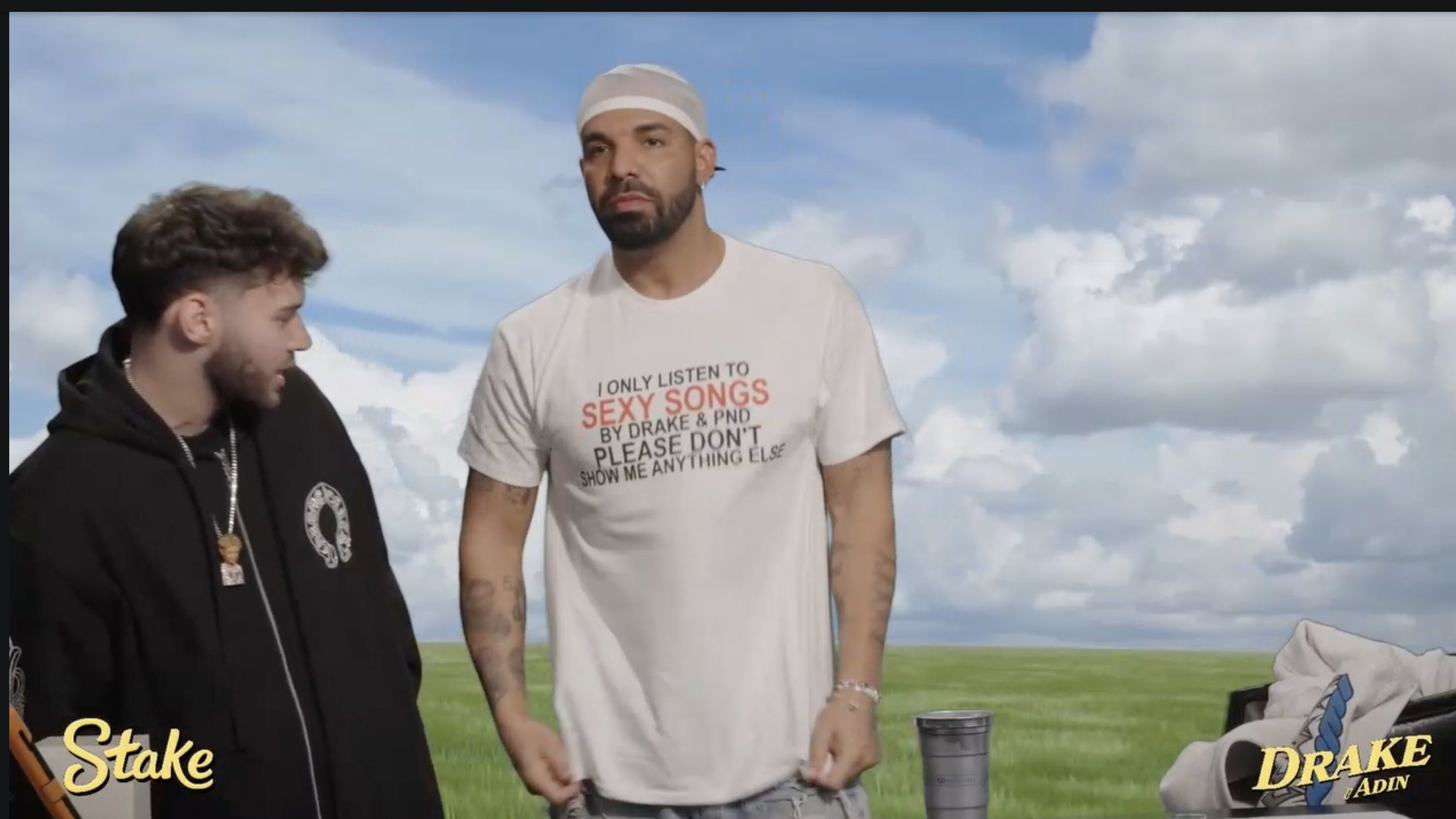

Post Malone Closes Coachella With Headlining Set Blending Hip-Hop and Country #hiphop Drake Confirms During Adin Ross Stream He’s Working On A New Solo Album #Drake

Drake Confirms During Adin Ross Stream He’s Working On A New Solo Album #DrakeHow to Watch Drake and Adin Ross' 'Stake vs. Drake and Ad... #Drake

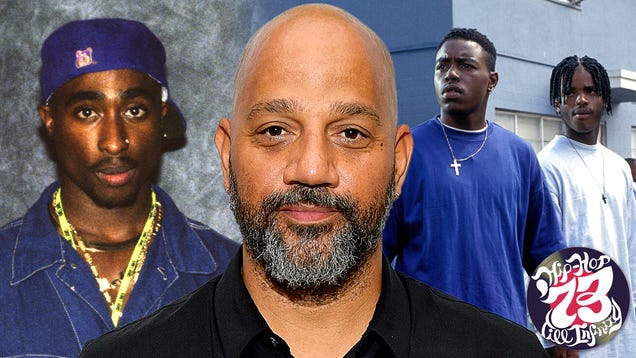

Director Allen Hughes on the power of hip-hop, Menace II Society, and forgiving Tupac #hiphop

theavclub August 28, 2023

hip-hop 15

This story is part of our new Hip-Hop: ’73 Till Infinity series, a celebration of the genre’s 50th anniversary.Menace II Society, which celebrated the 30th anniversary of its theatrical release in May, was not the first urban drama to capture the nation’s attention in the late 1980s and 1990s, but it was among the…Read more...

, which celebrated the 30th anniversary of its theatrical release in May, was not the first urban drama to capture the nation’s attention in the late 1980s and 1990s, but it was among the best. On the heels of (1988), (1991), and (1992), staked out turf where those venerable films (and others) dared not tread. It featured an unrelenting bleakness, an uncomfortable reality often referred to as “nihilistic,†according to co-director Allen Hughes. He credits that bleakness, in part, for the film’s success, but “biographical†is the word he prefers, referring to the actual people and places the fictional film represented. , which premiered to near-universal acclaim at the 1993 Cannes Film Festival, currently comprises a sizable and estimable portion of Allen Hughes’ legacy. His work with the late rapper and poet Tupac Shakur takes up another large slice and not always for the right reason. Allen, along with his brother, Albert, directed Shakur’s first two music videos, and . But their friendship seemingly ended in 1993 when Shakur was fired during pre-production on and the late rapper retaliated by brutally assaulting Hughes, which . Thirty years later, in what can only be described as a poignant and magnanimous act of forgiveness and attempt at understanding, Hughes has directed , a five-part, Emmy-nominated documentary about Shakur and his mother, the Black Panther activist Afeni Shakur. spoke to Allen Hughes about , Tupac Shakur, and the crucial role that hip-hop played in bringing them together. : Oh, thank you. Thank you so much. I’m not sitting in this interview without hip-hop. There is no without hip-hop. There’s clearly no Tupac and without hip-hop. So the throughline is that thing we call hip-hop that has urgency and put punk rock out of business with its voice and its visceral nature. Two young Black boys from Detroit would have never been able to direct a movie at 20 years old without hip-hop being where it was in the culture at the time. Well, it’s interesting because if you weren’t from New York in the early days, there was nothing. It was really ’83, ’84, ’85 when you started feeling hip-hop nationally. Run-DMC and L.L. Cool J were the first to punch through. But Slick Rick and Dougie Fresh, Eric B. & Rakim, the Beastie Boys, this is all stuff we weren’t getting on the West Coast or in the Midwest. So none of us knew about the first 15 years (of hip-hop) because we weren’t in New York. Yeah, I remember from Run-DMC’s debut album all the way to ... then it very quickly started happening. By the time you get to 1988, just four years later, you’re looking at . That’s light years from . And that’s just four short years. When we look at punk rock, it was this little fringe thing that happened in white culture; then hip-hop immediately took over everywhere. Even the white communities back then—it was hip-hop. It wasn’t like white kids caught on later. Back then, 90 percent of the sales of those albums were white kids in suburbia. So I think that coming up in 1984, when we were 12, 13, 14 years old, just seeing what hip-hop did for race relations was the thing that struck me. Straight up. And what it did for self-possession is what struck me, too. Because you would have this attitude when you went around that you didn’t have before. You felt empowered. You felt like you were seeing representation that just didn’t exist before. It was everything for a young teenager to experience in real-time as it was being born and growing into what it would become. You have a whole wave of cinema and television that directly springs out of hip-hop. A whole generation of artists, writers, poets, and actors that would not be here if it weren’t for hip-hop first. So hip-hop as a vehicle has led more (Black and Brown) people to the promised land than any other genre known to history. Yeah. And keep in mind the films we were making, the two shorts in particular, and had the DNA of hip-hop. And when we got into music videos, fortunately and unfortunately, we only were able to book hip-hop music videos. To get that big George Michael music video wasn’t going to happen. So it was hip-hop that gave us space to work as professional filmmakers. I wanted to show what happened when that event decimated that community and what came out of it. The lack of resources and what it does to families and individuals so the audience would get a better understanding of what Caine was born into—hopelessness, basically. The reason why we made was we knew Black people would enjoy the film and be struck by the film, but we were more trying to reach white people, to get them to understand that these children, these boys and girls, are not animals that you see in your evening news. Yeah, no context. There’s a thing that happens when “someone†makes these decisions in a community, given the lack of opportunity, health care, education, all kinds of shit. Read more